¿Debe el documental político dejarse llevar por las emociones?

Por Eleni Ampelakiotou

(Texto publicado en el número 88 de la revista tv diskurs, 2019, TV Diskurs Link)

(Scroll down to read the English translation)

"Los sentimientos crean hechos", así es como Nikolaus Blome, jefe de política del periódico sensacionalista más importante de Alemania, Bild, esbozó el enfoque de la nueva revista semanal Bild Politik. El proyecto piloto no solo incluye secciones tradicionales como las de política interior o exterior, sino que cuenta además con los apartados Ira, Alegría y Curiosidad. Blome asegura que, aunque estas secciones cubren hechos y temas relevantes, se centran sobre todo en "las emociones subyacentes".[1] Lo que esto nos revela es que “emocionalizar” temas políticos complejos ya no se considera una práctica dudosa, condición necesaria si se quiere evitar caer en la visión del mundo simplona y plana que antaño ofrecieran los noticieros tradicionales, que demagógicamente se servían de las emociones con fines ideológicos. La emocionalización de lo político está directamente relacionada con el sistema de cuotas de “la televisión de los sentimientos”. Desde los talk shows basados en la confrontación a los reality shows, pasando por el "infoentretenimiento", se busca excitar e indignar a la audiencia, sirviéndose de las mismas estrategias manipuladoras de los movimientos populistas, los medios sociales o hashtags como #MeToo.

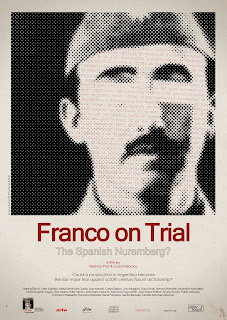

La larga disputa entre WDR (la mayor cadena de televisión pública de Alemania) y arte (cadena de televisión franco-alemana) en torno a la película LA CAUSA CONTRA FRANCO, de los directores y productores ganadores del premio Grimme Dietmar Post y Lucía Palacios, es, según Post, ilustrativa de la resistencia y el rechazo a los que hoy en día se enfrenta un documental político clásico que renuncie a caer en esa “emocionalización”. LA CAUSA CONTRA FRANCO es un trabajo basado en una impresionante investigación rigurosa y exhaustiva que, exponiendo las perspectivas tanto de víctimas como de victimarios, documenta el contexto histórico y jurídico de los esfuerzos de la justicia argentina para investigar y sentar en el banquillo a presuntos autores aún vivos de crímenes contra la humanidad cometidos por la dictadura franquista, tras el fracasado intento del juez Garzón en 2008 de que estos crímenes fueran juzgados por un tribunal español. La película se caracteriza por una neutralidad y un purismo libres de cualquier hermanamiento sentimental con las víctimas. Y esto fue precisamente lo que la cadena WDR reprochó a los directores.

El director Dietmar Post resume así la disputa: "Una versión bruta del documental LA CAUSA CONTRA FRANCO, coproducido por arte y WDR y emitido el 13 de febrero de 2018 en arte y poco después en Phoenix, había sido aceptada por la redacción de arte en 2017. Pero, para nuestra sorpresa, la redacción de WDR (coproductor minoritario), consideró que no podía emitir la película debido a su estilo, porque no era lo suficientemente emotiva y porque parecía demasiado una "película de autor". (...) La finalización de la película se retrasó un año entero. (...) Aunque expresamos en varias ocasiones estar dispuestos a discutir sobre una nueva versión, WDR retuvo el último pago para la producción, además de bloquear una garantía bancaria”.[2] Los cineastas, que habían ganado el premio Grimme en 2008 y habían sido nominados para el mismo premio en 2016 (la distinción más alta en la televisión alemana), no son precisamente principiantes en la creación de documentales. Por el contrario, su obra es fruto de una larga trayectoria comprometida en su estética, contenido y forma con el documental político clásico, cuya credibilidad radica en una investigación larga y rigurosa, en la presentación de contextos políticos e históricos complejos, en la sobriedad de la relación con sus protagonistas, en su renuncia a servirse de una dramaturgia “emocionalizadora y emocionalizante” y en tratar a protagonistas y espectadores como interlocutores autónomos: "Desde el punto de vista estético (...) queríamos poner de relieve nuestro modo de trabajo en todo momento: situaciones de conversación que intentar dar a todos los interlocutores las mismas oportunidades (...) sin distracciones. Las conversaciones deben ser lo más naturales posible (...) y permitir que hablen todas las partes, en este caso los querellantes y los acusados. (...) Intentamos guiarnos por lo que se nos dice y por el material de archivo, más que por una opinión preestablecida, (...) para que el espectador pueda así mismo formarse su propia opinión. Y contraponemos declaraciones antagónicas, como en un juicio".[3]

La redacción de WDR conocía bien el estilo documental de los cineastas. Además, contaban con un tratamiento detallado de 40 páginas: "En 2008, cuando el juez español Baltasar Garzón intentó por primera vez investigar los crímenes del franquismo, nos pusimos en contacto con él, con la esperanza de seguir el caso. Luego, en 2010, cuando Garzón fue inhabilitado 11 años de ejercicio profesional, la causa fue retomada por un grupo de abogados de derechos humanos argentinos, quienes organizaron la primera acción legal en Argentina (Darío Rivas, el primer querellante aparece en nuestra película). Desde el principio nos interesamos por los aspectos histórico y legal. (...) ¿Quiénes son los presuntos autores? ¿Cuál es el contexto político? ¿Quiénes son las víctimas? ¿Por qué son víctimas? ¿Qué crímenes se cometieron? ¿Qué pruebas históricas y forenses existen? ¿Qué órdenes había? Teníamos claro desde el inicio que no nos íbamos a centrar en las emociones (...) sino en la explicación y clarificación de los aspectos histórico, legal y forense (desde la introducción del análisis de ADN), más que en la emoción. (...)

También considerábamos muy importante describir con precisión casos paradigmáticos de cada una de las distintas fases del terror durante la dictadura, ya que son clave para la acusación: el golpe, la guerra, la represión de la posguerra, el exilio, los campos de concentración, la tortura, la represión general durante la larga dictadura, el tardofranquismo y la transición. (....) Procedimos de forma muy metódica, porque habíamos leído el auto de acusación primero. (...) Así que nuestro enfoque fue político e histórico desde el principio". El rechazo de la WDR obligó a los productores a buscar alternativas para sacar adelante la película: "Hasta ese momento siempre había sido posible llegar a un acuerdo con las cadenas de tv con las que habíamos trabajado. Como es lógico, los contratos de coproducción entre las cadenas y los productores preven precisamente que se llegue a un acuerdo. Así que dijimos, vale, si WDR no desea seguir adelante nos pondremos en contacto con otras cadenas. Phoenix se interesó de inmediato. (...) Después de una disputa que duró más de un año, WDR dio marcha atrás, pagó el último plazo y desbloqueó la garantía bancaria".[4]

Casi paralelamente a la emisión de LA CAUSA CONTRA FRANCO en arte, se estrenó en la sección Panorama de la Berlinale de 2018 una película sobre el mismo tema pero que parecía cumplir con la tan en voga emocionalización: EL SILENCIO DE OTROS, de los directores ganadores de un Emmy Almudena Carracedo y Robert Bahar, con Pedro Almodovár como productor ejecutivo. Tomando como ancla narrativa las esculturas del Mirador de la Memoria (obra del artista Francisco Cedenilla ubicada en el Valle del Jerte en homenaje a las víctimas de la guerra civil y de la dictadura franquista), la película arranca con una estética cargada de patetismo, en un contraluz deslumbrante. EL SILENCIO DE OTROS se abre con una toma de María Martín colocando un ramo de flores al borde de una autopista construida sobre una fosa común en la que está enterrado el cuerpo de su madre, asesinada por los franquistas. "Qué injusta es la vida. No la vida. Nosotros los humanos, somos injustos", dice María Martín, y de ahí se pasa a un plano de un cabritillo blanco como la nieve que pasta a la orilla de la carretera. Con este corte los directores convierten pues las palabras de María en una declaración sentimental sensacionalista generalizada ante la injusticia de la naturaleza humana. Este recurso se repetirá a lo largo de toda la película, con imágenes de animales y niños acompañando la narración. El ramo de flores se irá marchitando al borde de la carretera, como la esperanza de María Martín de exhumar algún día a su madre. Manos anónimas tocan las esculturas mientras suena música melancólica. El tono de patetismo y sentimentalismo establecido al principio continúa a través del uso del "pluralis majestatis" por la voz de la narración, que habla de un "nosotros" generalizado que representa a una generación de españoles cuyos padres aparentemente nunca hablaron de la dictadura franquista, dejando a las generaciones siguientes sumidos en la ignorancia. La supuesta amnesia de toda una generación que, al parecer, es incapaz de recurrir a ninguna otra fuente de información que no sean sus padres, es puesta en escena en tono didáctico e infantilizador mostrando una foto mientras se le explica al espectador que Franco es la persona que aparece al lado de Hitler, pero sin profundizar en las consecuencias políticas e históricas concretas del encuentro de estas dos figuras. Aunque la película intente entender la querella argentina y las dificultades a las que se enfrenta, ignora en gran medida las convicciones políticas de las víctimas, cuya oposición política fue precisamente la razón de su persecución y asesinato, excepto en el caso de miembros del movimiento estudiantil que fueron víctimas de tortura a fines de la década de 1960. Las víctimas se presentan principalmente como padres, madres, hijas e hijos, despojados de la identidad política que los había convertido en blanco del franquismo. Las dramáticas y emocionales historias de las víctimas están “pegadas” como si se tratase de “recortes” de protagonistas, editados unos tras otros de manera dinámica para obtener un efecto emotivo, hasta que una de las protagonistas cierra los ojos ante la cámara. A la abogada de derechos humanos argentina Ana Messuti no se le pregunta sobre temas legales, sino que es relegada a mera figura consoladora. La interjección de la jueza María Servini de Cubría, de la Sala Primera del Tribunal Penal Federal de Buenos Aires, de que hay que ser objetivos -pese a los conmovedores relatos de tortura y asesinato de las víctimas y sus familiares- fue lamentablemente ignorada por los directores. La película descuida esa objetividad, sirviéndose de imágenes manipuladoras y poniendo en escena la identificación con las víctimas. Por el contrario, los victimarios son demonizados como antagonistas morales y no se les presenta en su papel político como parte de la represión institucionalizada dirigida por el régimen. Por otro lado, la película ha sido criticada no sólo por la falsa representación de cómo se inicia la querella argentina y por la información inexacta sobre la financiación de las exhumaciones. La bisnieta de una de las víctimas, Aitana Vargas, se sintió obligada a escribir una carta al editor de la prestigiosa revista semanal The New Yorker para corregir la información tergiversada sobre una exhumación mostrada en la película: "Por mucho que aprecie el trabajo de los directores de EL SILENCIO DE OTROS, el documental no es un relato fiel de la historia de mi abuela (Ascensión Mendieta). Los restos que aparecen en el documental no son los de su padre (Timoteo Mendieta), sino de otra persona. Mucha gente dentro y fuera de España lo sabe porque numerosos medios de comunicación españoles e internacionales habían cubierto el tema. Mi familia tuvo que pasar por otra ronda de exhumaciones para encontrar a mi bisabuelo, que fue localizado, identificado y enterrado dignamente en Madrid unos meses después, en 2017".[5] Al ser interrogados por el periodista Willy Veleta sobre la manipulación de los hechos, los directores respondieron: "No es una película sobre hechos, sino sobre sentimientos, y el plano de Ascensión con el cráneo de su padre suponía el final perfecto. La familia parecía estar de acuerdo".[6]

La película no solo no hace referencia al contexto legal de la causa argentina ni a las significativas circunstancias políticas del fracaso de la primera causa abierta en España, sino que además equipara las dictaduras de Chile, Camboya y Ruanda sin hacer referencia a las diferencias específicas de cada una y manipula hechos en aras de la "coherencia" narrativa. A pesar de todo esto, EL SILENCIO DE OTROS ha sido celebrada por festivales y medios de comunicación impresos con la misma exaltación con la que habían elogiado en su día los reportajes de Claas Relotius, periodista alemán ganador de numerosos premios que había logrado el éxito gracias a sus artículos cargados de emoción, pero que “era un timador".[7] En un artículo sobre la Berlinale, Janosch Angene escribe sobre la película: "Es una montaña rusa emocional que va de la tristeza por lo ocurrido en el pasado a la esperanza, la alegría y la emoción por los éxitos que están tomando forma de forma lenta pero segura. Un documental tremendamente emotivo, profundo y relevante, que demuestra de forma convincente la importancia de la rehabilitación de las injusticias que se cometieron en España y en el mundo entero a lo largo de la historia. Después de cuatro años cubriendo la Berlinale, esta tarde he presenciado por primera vez una sala entera con lágrimas en los ojos aplaudiendo de pie a los directores".[8]

Cuestiones políticas e históricas complejas quedan reducidas a una especie de "injusticia" generalizada, hasta llegar a un final feliz bañado en lágrimas en el que un “nosotros” unificador evoca una experiencia universal consoladora. Con el objetivo de lograr un impacto emocional bajo un disfraz político, este estilo documental no considera al espectador un sujeto político, sino, tal y como Thomas Assheuer escribe en Zeit Online en respuesta a los relatos emocionalizados y en gran parte inventados y falsos de Claas Relotius, "alguien que necesita consuelo existencial". (...) La síntesis de realidad y ficción sirve para calmar aflicciones y tiene un efecto terapéutico. Aplaca los sentimientos y pone orden en el caos. Simplifica lo complicado y crea familiaridad con una realidad escandalosamente opaca. (...) El horror queda fuera".[9] Conmovido hasta las lágrimas, el público se cree en el lado correcto desde el punto de vista moral, al tiempo que aplaude su propia anulación como sujeto político. La idea de que el documental político debe tener un “final perfecto” no es otra cosa que una promesa sedante de salvación ya que la historia es un proceso sin final. Como dice Dietmar Post: "Esto contradiría lo que científicos, historiadores, psicólogos y filósofos nos explicaron hace ya tiempo. Por eso estamos a favor de una forma abierta del cine documental. La forma cerrada implica que se ha entendido el mundo. La forma cerrada afirma, pero rara vez prueba nada. Por otro lado, la forma cerrada es a menudo ideológicamente ciega”.

Nota: Lamentablemente, y a pesar de haber expresado su voluntad de participar en una discusión (correo electrónico de 9.01.19), la directora Almudena Carracedo no volvió a reaccionar después de haberle enviado preguntas específicas.

________________

[1] Huber, Joachim: Política con sentimiento, "Bild Politik": Springer inicia el proyecto piloto, 14.12.2018,

https://www.tagesspiegel.de/gesellschaft/medien/politik-mit-gefuehl-bild-politik-springer-startet-testlauf/23763442.html

[2] Cita tras un intercambio escrito con Dietmar Post en enero de 2019

[3] ibíd.

[4] ibíd.

[5] Vargas, Aitana: La historia de mi abuela debe ser contada, querido Editor del New Yorker, 11.01.2019 https://medium.com/@AitanaVargas/my-grandmothers-story-must-be-told-55623f5c98c5

[6] Veleta, Willy: Tres errores de 'El silencio de otros', Revista Contexto, Nr. 195, 14. 11. 2018,

https://ctxt.es/es/20181114/Politica/22919/errores-en-el-documental-el-silencio-de-otros-willy-veletavictimas-del-franquismo.htm

[7] Carbajosa, Ana: El escándalo ‘Der Spiegel’: paren la rotativa, todo es mentira

https://elpais.com/elpais/2019/02/12/eps/1549973689_120344.html

[8] Angene, Janosch: Berlinale Filmkritik : El silencio de otros, de Almudena Carracedo y Robert Bahar, en Berliner Film- und Fernsehverband, marzo de 2018

http://www.berliner-ffv.de/index.php/aktuell/film-aktuell/42-berlinale-filmkritik-the-silence-of-others-von-almudena-carracedo-und-robert-bahar

[9] Assheuer, Thomas: El mundo como reportaje, en ZEIT ONLINE, 26.12. 2018

https://www.zeit.de/2019/01/journalismus-reportagen-wirklichkeit-aufklaerung-claas-relotius

a text by Eleni Ampelakiotou

(The original text was published in the German magazine TV Diskurs, Heft 88, 2019)

“Feelings make facts” stated Nikolaus Blome, political editor of Germany’s largest tabloid Bild while outlining the approach for the pilot run of the weekly magazine Bild Politics, whose section headings Anger, Joy and Curiosity are a departure from the classic categories of domestic and foreign policy. Although it purports to be about facts and relevant subjects, it’s actually much more “about the underlying emotions”. 1) What this reveals is that it’s no longer considered questionable to emotionalise complex political subjects and simplify issues like in the old weeklies, which used emotions as demagogues for ideological purposes. The emotionalisation of political subjects is related to the ratings-winning genre of ‘Affektfernsehen’ (TV that aims to arouse an emotional response). From confrontational talk shows, to reality TV and ‘infotainment’, it harnesses the potential to stir up and outrage the audience, also deployed by the manipulative strategies of populist movements, social media generated shitstorms or hashtags like #MeToo. The year-long editorial dispute between WDR (Germany’s largest public broadcasting institution) and arte (Franco-German TV network) over the film FRANCO ON TRIAL: THE SPANISH NUREMBERG by Grimme prizewinning directors and producers Dietmar Post and Lucia Palacios could be seen (according to Post) as illustrative of the editorial obstacles faced by a classic political documentary film that doesn’t use the emotionalising approach. Based on impressively thorough research and the aim to present the perspectives of victims as well as perpetrators, FRANCO ON TRIAL documents the historical and legal background to efforts by the Argentinian judiciary to prosecute living alleged perpetrators of crimes against humanity under Franco’s dictatorship, following the failure of the attempt to bring the case to trial in a Spanish court in 2008. WDR even reproached the directors for the film’s objectivity and purism, free from any sentimental bias towards the victims. In a discussion, filmmaker Dietmar Post explained the dispute: “The documentary film FRANCO ON TRIAL, co-produced by arte and WDR, broadcast on 13.2.2018 on arte and soon after on Phoenix, had been given the green light by arte editors at WDR in 2017. Surprisingly, the editorial team at WDR (the budgetary minority co-partner), declared the film ‘unbroadcastable’ due to its style, because it wasn’t “emotionalising” enough and seemed too much of an “auteur film”. (...) So completion of the film was delayed by a whole year. (...) Although we’d made it clear we would be willing to discuss a shorter version, WDR withheld the last installment of funding for the production. A bank guarantee was also blocked.” 2) The filmmakers, who had won the Grimme prize in 2008 and received a nomination in 2016, are scarcely newcomers to documentary; their body of work exemplifies the classic political documentary film, in its aesthetics, content and form, its credibility based on in-depth research and its presentation of complex political and historical contexts, objective, sober distance from all its protagonists and refusal to use emotionalising, tension-creating dramaturgy and treatment of both protagonists and viewers as autonomous counterparts. “Aesthetically we wanted (...) to reveal our working approach at every point: conversational situations that give everyone the same opportunities (...) no distractions. Keeping the conversational situation as natural as possible (...). The plaintiffs must be allowed to speak, so too must the alleged perpetrators. (...) We should be guided by what we’re told and by the archive material, rather than a preformed opinion. (...) So the viewer can form their own impression. Testimonies stand against testimonies.” 3)

WDR’s editors were well aware of the filmmakers’ documentary approach. Furthermore, they had a detailed 40 page account of the filmmaking process: “In 2008, when the Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón first tried to bring the case to court, we contacted him, hoping to follow the trial. Then in 2010, when Garzón was politically sidelined by a 11 year ban from professional practice, the cause was picked up by human rights lawyers, who organised the first legal action in Argentina (Darío Rivas, the first plaintiff appears in our film). From the outset we were interested in the historical and legal aspects. (...) Who are the alleged perpetrators? What’s the political context? Who are the victims? Why are they victims? What crimes were committed? What historical and forensic evidence exists? What orders were there? From the outset we sought to focus on the historical, legal and (since the introduction of DNA analysis) forensic aspects, rather than the emotions. (...) It was also important to us to give an accurate description of paradigmatic cases in the separate phases of the terror, which are very important for the prosecution: the coup, war, postwar repression, exile, concentration camp, torture, general repression during the long dictatorship, the late stage of Francoism and the transitional phase after Franco’s death (...) Our approach was very methodical, because we had read the bill of indictment first. (...) So a political and historical approach from the outset.” The rejection by WDR forced the producers to find new ways: “Until that point it had always been possible to reach an agreement with the broadcasters. Contracts between broadcasters and producers aim to find an agreement. So we said “ok, if WDR doesn’t want it we’ll contact other broadcasters”. Phoenix was interested at once. (..) After a dispute lasting over a year, WDR backpedalled, paid the last installment of funding and the bank guarantee was authorised.” 4)

At almost the same time as FRANCO ON TRIAL was broadcast on arte, a film about the same subject, but meeting the demand for emotionalisation, was premiered as part of the Panorama Programme of the Berlinale 2018: THE SILENCE OF OTHERS, by Emmy winning directors Almudena Carracedo and Robert Bahar, with Pedro Almodovár as executive producer. Taking as its narrative anchor ‘Mirador de la Memoria’, the monumental sculptures in Valle del Jerte by artist Francisco Cedenilla for the victims of the civil war and Franco’s dictatorship, using an emotive aesthetic and shot with dazzling backlight, THE SILENCE OF OTHERS opens with a shot of María Martín laying a bunch of flowers at the edge of a motorway built on top of a mass grave where the body of her mother, murdered by Francoists, is buried. “How unjust life is. Not life. We humans, we are unjust” says María Martín and her statement is accompanied by a shot of a snow-white baby goat, grazing on the edge of the road, turning it into a generalised sentimental statement about the injustice of humanity. Similarly, footage of animals and children repeatedly accompanies the narration. The bunch of flowers withers by the roadside like María Martín’s hopes of exhuming her mother. Anonymous hands touch the sculptures as melancholy music plays. The tone of pathos and sentimentality established by the opening continues in the use of the ‘royal we’ by the off-camera commentary, which becomes a generalising ‘we’ standing for a generation whose parents apparently never spoke about Franco’s dictatorship, leaving the subsequent generations with a sense of ignorance. The supposed amnesia of a whole generation, seemingly unable to draw on any sources of information other than their parents, is represented in the didactic, infantilising tone as it fades into a photo and explains to the viewer that Franco is the person beside Hitler, but neglects to explain the concrete political and historical consequences of their ‘acquaintance’. Even though the film tries to understand the processes and impediments in the Argentinian legal action, it largely ignores the political convictions of the victims, whose political opposition was the reason for their persecution and murder, except in the case of the members of the student movement who were victims of torture at the end of the 1960s. The victims are presented primarily as fathers, mothers, daughters and sons, detached from the political identity which had made them targets under Franco. The victims’ emotional dramas are strung together like cuttings of protagonists, edited together for emotive effect, until one of the protagonists feels the need to close her eyes in front of the camera. The Argentinian human rights lawyer Ana Messuti isn’t so much questioned about the legal issues, as used as a consoling authority. The interjection by judge María Servini de Cubría from the First Chamber of the Federal Criminal Court in Buenos Aires that one must remain objective despite victims’ emotionally affecting accounts of torture and the murder of their relatives, was unfortunately ignored by the directors. With its manipulative imagery and emotional bias towards the victims the film neglects such objectivity. The perpetrators are demonised as moral antagonists and not portrayed in their political role as part of the institutionalised repression led by the regime. There was criticism of the film’s false portrayal of the start of the Argentinian legal action and the inaccurate information regarding the financing of the exhumations. The great granddaughter of one victim, Aitana Vargas, felt compelled to write a letter to the New Yorker highlighting the film’s misrepresentation of an exhumation: “As much as I appreciate the work of the directors of ‘The Silence of Others’, the documentary film does not present a realistic portrait of my grandmother’s story (Ascensión Mendieta (author’s annotation)). The body she is looking at in the documentary footage is not that of her father (Timoteo Mendieta (author’s annotation)). It was someone else’s body. Many people in Spain and outside my country know that because many Spanish and international media sources have reported on it. My family had to go through another round of exhumations to find my great grandfather, who was localised, identified and given a dignified, non-religious burial in Madrid some months later in 2017.” 5) Questioned by journalist Willy Veleta about manipulation of the facts, the directors replied: “It’s not a film about facts, but about feelings and Ascensión’s view that the skull was that of her father, provides the perfect ending. Her family seemed to agree." 6)

Despite the inadequate portrayal of the legal context of the Argentinian prosecution, the politically significant circumstances of the failure of the first legal action in Spain, the leveling of specific differences between political dictatorships in Chile, Cambodia and Rwanda, and the manipulation of known facts for the sake of narrative ‘coherence’, THE SILENCE OF OTHERS was highly praised at both festivals and in the print media. A parallel can be seen here with the high profile case of Claas Relotius, a journalist who achieved success and won prizes for his emotionalising articles, but was found to have “falsified his articles on a grand scale.”7) This scandal revealing the emotionalisation of stories in the media has been seen as a moment of crisis for German journalism.

In an article about the Berlinale screening of THE SILENCE OF OTHERS Janosch Angene writes: “It’s an emotional rollercoaster from sorrow about the past, to hope, joy and emotions at the successes that are slowly but surely taking shape. A tremendously emotional, profound and important documentary film, which convincingly demonstrates the importance of the reappraisal of injustices in the history of Spain and the whole world. In the last four years of the Berlinale, this afternoon was the first time I’ve seen a whole auditorium with tears in their eyes give the directors a standing ovation.” 8) Complex political and historical issues are simplified to a generalised ‘injustice’, suspended in a tear-jerking happy end, with the unifying ‘we’ evoking a consoling world experience. Aiming for emotional impact in the guise of politics, this documentary style does not address the viewer as a political entity, but as Thomas Assheuer writes in Zeit Online with reference to the Relotius case, “as one needing existential consolation. (...) The synthesis of fact and fiction serves the pastoral life affirmation and has a therapeutic effect. It stabilises the feelings and brings order to chaos. It makes what is complicated simple and creates familiarity with shamefully opaque reality. (...). Horror is excommunicated.” 9) Moved to tears, the viewers believe themselves to be on the morally safe side, while also applauding their own disenfranchisement as a political entity. The idea that political documentary films should have a ‘perfect ending’ is a sedating promise of salvation, because history is a never-ending process, as Dietmar Post says: “It would contradict what scientists, historians, psychologists and philosophers have long declared. That’s why we favour the open form of documentary film. The closed form means that the world has been comprehended. The closed form asserts, but rarely proves something. And the closed form is often ideologically blind.”

Note: Unfortunately, despite the director Almudena Carracedo’s willingness to participate in a discussion (email on 9.01.19), she no longer responds to specific questions.

1) Huber, Joachim: Politik mit Gefühl, „Bild Politik“: Springer startet Testlauf, 14.12.2018,

https://www.tagesspiegel.de/gesellschaft/medien/politik-mit-gefuehl-bild-politik-springer-startet-testlauf/23763442.html

2) from a discussion and written exchange with Dietmar Post in January 2019

3) ibid.

4) ibid.

5) Vargas, Aitana: My grandmothers story must be told, Dear Editor of the New Yorker, 11.01.2019

https://medium.com/@AitanaVargas/my-grandmothers-story-must-be-told-55623f5c98c5

6) Veleta, Willy: Tres errores de 'El silencio de otros' in ctxt, Revista Contexto, Nr. 195, 14. 11. 2018,

https://ctxt.es/es/20181114/Politica/22919/errores-en-el-documental-el-silencio-de-otros-willy-veletavictimas-del-franquismo.htm

7) Connolly, Kate (19 December 2018). "Der Spiegel says top journalist faked stories for years". The Guardian and "The Relotius Case: Answers to the Most Important Questions". Spiegel Online. 19 December 2018.

8) Angene, Janosch: Berlinale Filmkritik : The silence of others’ von Almudena Carracedo und Robert Bahar, in Berliner Film- und Fernsehverband, Der Berufsverband der Berliner Filmbranche, March 2018

http://www.berliner-ffv.de/index.php/aktuell/film-aktuell/42-berlinale-filmkritik-the-silence-of-others-von-almudena-carracedo-und-robert-bahar

9) Assheuer, Thomas: Die Welt als Reportage, in ZEIT ONLINE, 26.12. 2018, DIE ZEIT 01/2019, 27.12.2018

https://www.zeit.de/2019/01/journalismus-reportagen-wirklichkeit-aufklaerung-claas-relotius/seite-2

DEUTSCH

Der politische Dokumentarfilm - powered by emotion?

„Gefühle schaffen Fakten“, skizzierte „Bild“-Politikchef Nikolaus Blome den Ansatz für den Testlauf des Wochenmagazins „,Bild Politik‘, das jenseits klassischer Ressorts wie Innen- oder Außenpolitik“, die Rubriken „Ärger“, „Freude“ und „Neugier“ führt. Es ginge zwar um Fakten und relevante Themen, doch noch viel mehr ginge es „um die Emotionen, die darunterliegen“. 1) Bemerkenswert hierbei, dass die Emotionalisierung komplexer politischer Sachverhalte als fragwürdige Kategorie nicht mehr in Zweifel gezogen wird, was angebracht wäre, wollte man nicht erneut in den Weltvereinfachungs-Gestus alter Wochenschauen verfallen, die Emotionen demagogisch für ideologische Zwecke nutzten. Die Emotionalisierung des Politischen orientiert sich am Quotengenre des ‚Affektfernsehens’. Von konfrontativen Talkshows, über Reality TV bis Infotainment zielt es auf das Erregungs- und Empörungspotenzial des Publikums, welches von manipulativen Strategien populistischer Bewegungen ebenso bedient wird, wie von Shit-storms sozialer Netzwerke oder hashtags wie MeToo. Die einjährige redaktionelle Auseinandersetzung zwischen WDR und arte um den Film FRANCO ON TRIAL/ FRANCO VOR GERICHT: DAS SPANISCHE NÜRNBERG? der Adolf Grimme Preis prämierten Regisseure und Produzenten Dietmar Post und Lucia Palacios, könnte laut Dietmar Post als Indiz wahrgenommen werden, gegen welche redaktionellen Widerstände sich ein klassisch politischer Dokumentarfilm inzwischen behaupten muss, der auf affektgeschwängerte Inszenierungen verzichtet. FRANCO ON TRIAL dokumentiert mit beeindruckender Recherchegenauigkeit und um Darstellung der Perspektiven von Opfern und Tätern bemüht, den historischen und juristischen Kontext der Anstrengungen der argentinischen Justiz, noch lebenden mutmaßlichen Tätern der Franco Diktatur aufgrund begangener Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit den Prozess zu machen, nachdem der Versuch 2008, die Verbrechen vor einem spanischen Gericht aufzuklären, gescheitert war. Gerade die Sachlichkeit und der von jeder sentimentalen Verbrüderung mit den Opfern befreite Purismus des Films wurde den Regisseuren vom WDR zum Vorwurf gemacht. Im Gespräch erläutert einer der Filmemacher, Dietmar Post, den Verlauf der Auseinandersetzung: „Der von arte und WDR coproduzierte Dokumentarfilm FRANCO VOR GERICHT, ausgestrahlt am 13.2.2018 auf arte und kurz darauf auf Phoenix wurde von der beim WDR zuständigen arte Redaktion im Jahr 2017 abgenommen. Überraschenderweise wurde jedoch der Film von der WDR-Redaktion, dem budgetär minoritären Co-Partner, aufgrund seiner „Machart“ für nicht sendbar erklärt, weil er zu wenig „emotionalisierend“ und zu sehr als „Autorenfilm“ erschien. (...)Die Fertigstellung des Filmes wurde so um ein volles Jahr behindert. (...)Trotz unserer signalisierten Gesprächsbereitschaft bezüglich einer gekürzten Fassung verweigerte der WDR die letzte Finanzierungsrate für die Produktion. Darüberhinaus wurde auch eine Bankbürgschaft blockiert.“ 2) Die im Jahr 2008 Grimme-Preis prämierten und 2016 nominierten, Filmemacher sind keine dokumentarischen Newcomer sondern weisen ein Gesamtwerk auf, das ästhetisch, inhaltlich und formal, dem klassischen politischen Dokumentarfilm verpflichtet, seine Glaubwürdigkeit aus eingehender Recherche und Darstellung komplexer politischer und historischer Zusammenhänge, sachlich nüchterner Distanz zu allen Protagonisten und dem Verzicht auf emotionalisierende Spannungs-Dramaturgie generiert und Protagonisten wie Zuschauer als autonomes Gegenüber wahrnimmt: „Ästhetisch wollten wir (...) eine Offenlegung unserer Arbeitsweise zu jedem Zeitpunkt: Gesprächssituationen, die allen Beteiligten eine Gleichberechtigung geben. (...) ohne Ablenkungen. eine möglichst natürliche Gesprächssituation(...). Die Kläger müssen reden dürfen und die mutmaßlichen Täter ebenso. (...) Das Gehörte und das Archivmaterial sollte uns leiten und nicht eine vorgefasste Meinung. (...) So kann der Zuschauer sich selber ein Bild machen. Aussagen stehen gegen Aussagen.“ 3)

Die dokumentarische Handschrift der Filmemacher war der WDR Redaktion hinlänglich bekannt. Zudem lag der Redaktion ein 40 seitiges detailliertes Exposé vor, das das filmische Vorhaben eingehend darlegte: „Bereits 2008, als der spanische Richter Baltasar Garzón erstmals die Fälle vor Gericht bringen wollte, kontaktierten wir ihn und wollten diesen möglichen Prozess begleiten. Als dann 2010 Garzón politisch, mit einem 11jährigen Berufsverbot, kaltgestellt wurde, griffen Menschenrechtsanwälte das Thema auf und organisierten die erste Klage in Argentinien (der erste Kläger Darío Rivas ist in unserem Film). Wir haben uns von Beginn an für die historischen und juristischen Aspekte interessiert. (...) Wer sind die mutmaßlichen Täter? Welcher politische Kontext lag vor? Wer sind die Opfer? Und warum sind sie Opfer? Welche Verbrechen wurden begangen? Welche historischen und forensischen Beweise gibt es? Welche Befehle gab es? D.h. wir haben von Beginn an nicht auf Emotionen (...) sondern auf die Erklärung/Klärung von historischen, juristischen und seit der Einführung der DNA-Analysen auf forensische Aspekte wert gelegt. (...) Auch war uns wichtig, paradigmatische Fälle der einzelnen Phasen des Terrors genau zu beschreiben, weil sie für die Anklage von großer Bedeutung sind: Putsch, Krieg, Nachkriegsrepression, Exil, KZ, Folter, allgemeine Repression während der langen Diktatur, die Spätphase des Frankismus und die Phase der Transici

ón nach Francos Tod(...) Wir sind sehr methodisch vorgegangen, weil wir im Vorfeld genau die Anklageschrift gelesen hatten. (...) Ein politischer und historischer Ansatz von Beginn an.“ Die Ablehnung des WDR zwang die Produzenten neue Wege zu gehen: „Bisher konnte man sich mit den Sendern immer einig werden. So sehen es die Verträge zwischen Sendern und Produzenten ja auch vor, dass man sich einigt. Also sagten wir uns, nun gut, wenn der WDR nicht will, dann kontaktieren wir andere Redaktionen. Phoenix war dann sofort interessiert. (..) Nach über einjährigem Kampf hat dann der WDR zurückgerudert, das Geld wurde bezahlt und auch die Bürgschaft freigegeben.“ 4)

Fast zeitgleich zur arte Ausstrahlung von FRANCO ON TRIAL wurde ein Film mit derselben Thematik im Panorama Programm der Berlinale 2018 uraufgeführt, der die Forderung nach Emotionalität zu erfüllen schien: THE SILENCE OF OTHERS, der Emmy prämierten Regisseure Almudena Caraccedo und Robert Bahar, unterstützt durch Pedro Almodovár als executive producer. Ausgehend vom Mirador de la Memoria, den monumentalen Skulpturen des Künstlers Francisco Cedenilla, für die Opfer des Bürgerkriegs und der Franco Diktatur, im Valle del Jerte, als narrativem Anker, in pathetischer Ästhetik in gleißendem Gegenlicht eingefangen, inszeniert THE SILENCE OF OTHERS zu Beginn, die Niederlegung eines Blumenstraußes von María Martín am Rand einer Schnellstraße, unter der ihre von Francisten ermordete Mutter in einem Massengrab liegt. Ein persönliches Bekenntnis María Martíns: „How unjust life is. Not life. We humans we are unjust“, flankiert mit einem Schnitt auf ein niedlich schneeweisses, am Strassenrand grasendes Zicklein, wird so von der Regie zur sentimental generalisierten Ungerechtigkeit menschlicher Natur boulevardisiert. Aufnahmen von Tieren und Kindern, werden auf dieselbe Weise im weiteren Verlauf wiederholt in die Narration montiert. Der Blumenstrauß wird am Autobahnrand verdorren, wie die Hoffnung María Martíns, ihre Mutter exhumieren zu können, während anonyme Hände die Skulpturen abtasten, mit wehmütiger Musik untermalt. Die bereits am Anfang gesetzte Tonalität zwischen Pathos und Sentiment setzt sich fort im Pluralis majestatis eines Off-Kommentars, der weiter generalisierend im „Wir“ eine Generation vereinnahmt, deren Eltern vermeintlich niemals von der Franco Diktatur sprachen und somit nachfolgende Generationen in einen Zustand der Ahnungslosigkeit versetzten. Die behauptete Amnesie einer gesamten Generation, die sich offenbar keiner anderen Informationsquelle als den Eltern zu bedienen wusste, wird inszeniert in didaktisch infantilisierter Tonalität, die den Zuschauern durch Einblendung eines Fotos erklärt, dass Franco, die Person neben Adolf Hitler ist, unter Vernachlässigung jeglicher konkreten politischen und historischen Konsequenzen dieser „Bekanntschaft“. Auch wenn der Film versucht das Procedere und die Hindernisse der argentinischen Klage nachzuvollziehen, so übergeht er, außer bei den studentenbewegten Folteropfern Ende der 60erJahre, zum Großteil die politischen Überzeugungen der Opfer, deren politische Gegnerschaft gerade Ursache ihrer Verfolgung und Ermordung war. Die Opfer werden vornehmlich als Väter, Mütter, Töchter und Söhne jenseits einer politischen Identität präsentiert, die sie jedoch gerade zur Zielscheibe des Franco-Regimes machte. Die emotionalen Dramen der Opfer reihen sich zu Schnipseln von Protagonisten, zu Sprech-und Emotionsblasen dynamisch montiert, bis eine Protagonistin selbst die Augen vor der Kamera verschließt. Die argentinische Menschenrechtsanwältin Ana Mesuti wird weniger zur juristischen Sachlage befragt, sondern als trostspendende Instanz inszeniert. Leider bleibt der Einwurf der Richterin María Servini de Cubría von der Ersten Kammer des Bundesstrafgerichts in Buenos Aires, von der Regie ungehört, dass es zwar emotional aufrührend sei, wenn die Opfer von Folterungen und Tötungen ihrer Verwandten berichten, dass man aber dennoch objektiv bleiben müsse. Diese Objektivität lässt der Film durch seine manipulative Bildsprache und emotionale Verbrüderungs-inszenierung von Opfern und Regie vermissen. Demgegenüber werden die Täter als moralische Antagonisten dämonisiert und nicht in ihrer politischen Funktion innerhalb einer regierungskonformen institutionalisierten Repression politischer Gegner portraitiert. Kritik regte sich gegen den Film nicht nur bezüglich der falschen Darstellung des Beginns der argentinischen Klage und den Fehlinformationen hinsichtlich der Finanzierung der Exhumierungen. Die Urenkelin eines Opfers, Altana Vargas, sah sich In einem offenen Brief an den New Yorker gezwungen, die im Film gezeigten Bilder einer Exhumierung wahrheitsgemäß zu korrigieren: „So sehr ich die Arbeit der Regisseure von ‚The Silence of Others’ schätze, misslingt es dem Dokumentarfilm ein reales Portrait der Geschichte meiner Großmutter (Ascensión Mendieta (Anm.)) zu präsentieren. Der Körper, auf den sie in den dokumentarischen Aufnahmen blickt, war nicht der ihres Vaters (Timoteo Mendieta (Anm.)). Es war der Körper eines Anderen. Viele Menschen in Spanien und über die Grenzen meines Landes hinaus wissen das, da zahlreiche spanische und auswärtige Medien darüber berichteten. Meine Familie musste noch eine weitere Exhumierungsrunde durchlaufen, um meinen Urgroßvater zu finden, der Monate später lokalisiert, identifiziert und in einer nicht religiösen Zeremonie 2017 in Madrid eine würdige Bestattung fand“. 5) Vom Journalisten Willy Veleta auf diese Modellierung der Faktenlage angesprochen entgegnete die Regie: „Es ist kein Film über Daten, sondern über Gefühle und diese Einstellung mit Ascención, dass der Totenschädel der ihres Vaters war, ist das perfekte Ende und die Familie schien einverstanden zu sein." 6)

Trotz mangelnder Darstellung des juristischen Kontexts der argentinischen Anklage, der politisch bedeutsamen Umstände des Scheiterns der ersten Anklage in Spanien, der Nivellierung spezifischer Unterschiede politischer Diktaturen in Chile, Kambodscha und Ruanda, sowie der Modellierung von bekannten Fakten hinsichtlich einer narrativen „Stimmigkeit“, wurde THE SILENCE OF OTHERS, auf Festivals und in Printmedien, ähnlich affektgeschwängert gefeiert wie die Reportagen von Claas Relotius. „Es entsteht ein Auf und Ab aus Trauer angesichts der Vergangenheit und Hoffnung, Freude und Rührung angesichts der Erfolge, die sich langsam aber sicher einstellen. Ein ungemein emotionaler, tiefgründiger und bedeutender Dokumentarfilm, der eindrucksvoll aufzeigt, wie wichtig die Aufarbeitung von Unrecht in der Geschichte Spaniens und der ganzen Welt ist. In den vergangenen vier Jahren Berlinale habe ich bis heute Nachmittag noch nie erlebt, dass sich der gesamte Saal mit Tränen in den Augen zu einer Standing Ovation für die Regisseure erhebt.“ 7)

Komplexe politische und historische Sachverhalte werden eingeebnet hinsichtlich eines verallgemeinernden „Unrechts“, aufgehoben in einem sich im tränenbeseelten Happy End tröstlicher Welterfahrung verbrüdernden „Wir“. Diese auf Affekte und Emotionen zielende dokumentarische Prosa, die sich politisch maskiert, spricht den Zuschauer jedoch nicht als politisches Subjekt an, sondern wie die Reportagen von Claas Relotius „ als einen existenziell Trostbedürftigen. (...) Die Fakt-Fiktion-Synthesen dienen der pastoralen Daseinsberuhigung und wirken wie eine Therapie. Sie stabilisieren Gefühle und bringen Ordnung ins Chaos. Sie machen das Komplizierte einfach und schaffen Vertrautheit mit einer skandalös unverständlichen Realität (...). Der Schrecken ist gebannt.“ 8) Das zu Tränen gerührte Kollektiv wähnt sich hierbei auf der moralisch sicheren Seite, während es gleichzeitig seiner eigenen Entmündigung als politisches Subjekt applaudiert. Die Vorstellung, dass politische Dokumentarfilme „ein perfektes Ende“ haben sollen, ist ein sedierendes Heilsversprechen, weil Geschichte ein nie abgeschlossener Vorgang ist, wie Dietmar Post ausführt: „Es würde dem widersprechen, was Wissenschaftler, Historiker, Psychologen und Philosophen längst erklärt haben. Deshalb favorisieren wir die offene Form des Dokumentarfilms. Die geschlossene Form meint, die Welt verstanden zu haben. Die geschlossene Form behauptet, aber beweist selten etwas. Und die geschlossene Form ist oft ideologisch blind“.

Anmerkung: Leider hat die Regisseurin Almudena Carracedo trotz ihres Interesses an einem Gespräch (mail vom 9.01.19), auf konkrete Fragen nicht mehr reagiert.

1)Huber, Joachim: Politik mit Gefühl, „Bild Politik“: Springer startet Testlauf, 14.12.2018,

https://www.tagesspiegel.de/gesellschaft/medien/politik-mit-gefuehl-bild-politik-springer-startet-testlauf/23763442.html

2) zitiert nach einem Gespräch und Schriftwechsel mit Dietmar Post, im Januar 2019

3) ebenda

4) ebenda

5)Vargas, Aitana: My grandmothers story must be told, Dear Editor of the New Yorker, 11.01.2019

https://medium.com/@AitanaVargas/my-grandmothers-story-must-be-told-55623f5c98c5

6)Veleta, Willy: Tres errores de 'El silencio de otros' in ctxt, Revista Contexto, Nr. 195, 14. 11. 2018,

https://ctxt.es/es/20181114/Politica/22919/errores-en-el-documental-el-silencio-de-otros-willy-veletavictimas-del-franquismo.htm

7) Angene, Janosch: Berlinale Filmkritik : The silence of others’ von Almudena Carracedo und Robert Bahar, in Berliner Film- und Fernsehverband, Der Berufsverband der Berliner Filmbranche, März 2018

http://www.berliner-ffv.de/index.php/aktuell/film-aktuell/42-berlinale-filmkritik-the-silence-of-others-von-almudena-carracedo-und-robert-bahar

8) Assheuer, Thomas: Die Welt als Reportage, in ZEIT ONLINE, 26.12. 2018, DIE ZEIT 01/2019, 27.12.2018

https://www.zeit.de/2019/01/journalismus-reportagen-wirklichkeit-aufklaerung-claas-relotius/seite-2

Comments