SoundsXP reviews DVD "The Transatlantic Feedback"

http://soundsxp.com/artman2/publish/special/Monks_DVD_Transatlantic_feedback.shtml

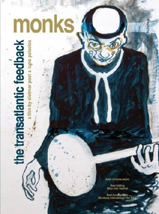

Monks - The Transatlantic Feedback | ||

‘The Transatlantic Feedback’ – now available for the first time in the UK as an official release (although it was originally released in 2008, when it won the Adolf Grimme Award) - tells the story of Monks, in their own words, with clips from the time: from their genesis, to revelation, to diaspora and the second coming. It’s a very human story – funny, sad, and triumphant – about how five ordinary guys came to make, albeit briefly, extraordinary music, far away and unheard of in their homeland, prophets unrecognised. It’s a great DVD, with superb extras. At the start of the film Hans Joachim Irmler, founder member of legendary Krautrock band Faust, tells us how at the age of 15 he saw Monks performing on German TV and was blown away: “The vitality, the minimalism, the hardness…there was nothing like it”. It was a world away from, and antidote to, the soporific sounds of the Beatles and the ‘unmentionable’ Rolling Stones. For him, it was an epiphany: without Monks there would have been no Faust. If people had understood it in 1966, he remarks, the 1968 revolution would have happened two years earlier. But it was too hard, too minimal…people didn’t ‘buy’ it, Monks were dissolved, heretics consigned to a footnote in musical history. Genesis The DVD covers the early days, with Gary Burger (guitar) and Eddie Shaw (bass), then serving in the US Army based in West Germany, meeting up to jam in the camp service club. They set up a band – The Torquays – as a way of breaking out of the confines of Army life and getting to meet German people. Once discharged they stayed on in Germany, continuing to play the bars and clubs wherever they could. Now known as the 5 Torquays – and what was later to become Monks - Gary Burger (lead guitar, lead vocals), Eddie Shaw (bass guitar, vocals), Larry Clark (organ, vocals), Dave Day (rhythm gtr, later banjo for Monks, vocals) and Roger Johnston (drums, vocals), played popular stuff of the time: Kinks, Rolling Stones, and especially the Beatles. Beatlemania had hit Germany big time. But they were just one band amongst many - there was a lot of competition and they needed to develop their own show to stand out, the music wasn’t enough. By this time something else was happening to them. They all had Germans girlfriends and wives. They were now playing as civilians in clubs, no longer as GIs in GI bars. Consequently, they began to lose their American identity. And, arguably, the sense of being tied to a musical legacy, e.g. that which created rock’n’roll. They also realised that they all got along well, and that they could stay together to do a record. So they recorded a single – 'There She Walks' b/w 'Boys are Boys'. By their own admission it was not great, but at least it was a step in the right direction. They were also looking out to be spotted by possible managers or record companies. Revelation And it is at this point that two central characters in Monks' history appear - Karl-H Remy and Walther Niemann (neither appear in the film: Walther says that a good manager should always stay in the background, and Karl, long presumed dead but found to be alive during the making of the film, also refused to take part). They were not record company people but designers/artists/theorists who said they were looking for a band/project. That project was ‘monks’. At first, the band thought that Karl and Walther were crazy. They talked about power of communication, of images. They even drew up six rules of Monks' image, which included always were black, always be a Monk, never be a Torquay… The tonsure haircut was a reaction to the long, coiffured hair of the beat groups. Again the group weren’t sure, but one by one they did it. They donned black clothes, and wore rope for ties as if nooses. The reaction was remarkable and instant. It made them all feel completely different, alien. People would walk out of their way, and avoided eye contact. Karl and Walther also talked about making a primal music: that the emphasis should be placed on rhythm. There should be simple chord progressions, working for tension rather than melody. The guitar should be distorted, the organ shrieking and non-melodic. The drums should focus on tom-toms and not use cymbals. The rhythm guitar, now inaudible, was replaced by an electrified banjo. The lyrics were kept to a minimum and repetitive, the vocal variously screaming, shouting, speaking. The old Torquays material was deconstructed in this way – the chords reduced, the lyrics curtailed. All this was met with some scepticism – what the hell was this, they asked? It was not something the Rolling Stones would play or cover. In fact, nobody had played this sort of thing before. But they experimented – sometimes ad libbing and ranting: which is how the rant in ‘Monk Time’ came about. A demo was made and they were picked up by Polydor International. ‘Black Monk Time’ was recorded quickly, in 2 days, and the sound engineer describes how recording was not about single instruments but the total sound of the group, the main microphone used being an ambient one. At a loss for words the company representative describes it as an early form of heavy metal, so loud he had to walk outside to listen to it. Monks moved to Hamburg, then the beat music centre and where the Beatles had grafted away in their early years. Hamburg loved Monks. Perhaps it was more open minded – possibly because it is a port city and a melting pot – but outside of the city the reception to Monks' music was different, met by indifference, stunned faces or simply hate. This had an effect on the band: they were hated and they hated. They just wanted to play, get it over and done with, and move on to the next gig. Nor were they making much money from this. The LP didn’t sell and there was pressure to soften the hard sound – the resulting single 'Love Can Tame The Wild' b/w 'He Went Down To The Sea' moved away from Monks’ sound but it didn’t sell either. The management was crumbling too and without their guidance and support Monks felt lost. Doubt grew in their minds. They all drifted from the Monks image - stopped wearing black, grew their hair, weren’t Monks anymore. They were fighting, Larry and David coming to blows on the dance floor. Roger had had enough and quit. And that was that. It was the end of the experiment. As Gary observes, they were mostly normal, perhaps too normal, and you could not be normal to carry it off: you can’t just borrow the image, you have to own it. After a while, none of them wanted to own it anymore… It was 1967. Diaspora and second coming Monks moved back to the US, an angry country that was not the same one they had left. They had had seven years of culture shock in Germany and were facing another culture shock back in the US and had a hard time adjusting. Some felt Germany was their home and moved back but couldn’t adjust there. All were embarrassed to talk about Monks and the sense of failure they felt. They lost contact with each other, some drifted homeless, another got a job in IBM, another stayed on in music, they settled down…They, and the world, forgot about Monks. The LP languished in the remaindered bin in the catacombs of history. But that was until – like the discovery of the dead sea scrolls – the lost gospel was re-found and preached once more, by fans like Irmler who remembered seeing them on German TV and picked up by a new audience of fans introduced to Monks’ compelling primal music. It was a second coming. Not only was ‘Black Monk Time’ reissued but Monks were encouraged to get back together to play for fans and in America for the very first time. The DVD ends on a high note with their triumphant 1999 reunion gig in New York, where the likes of Genesis P Orridge and Jon Spencer are amongst the congregation of followers come to worship. It must have been redemptive for Monks because they continued to play gigs thereafter but, sadly, it is no longer possible to see original Monks: in 2004 Roger Johnston died, and Dave Day died in 2008. But Monks music lives on as a testament to an exciting experiment that challenged not only the perceptions of the time but which have a resonance today – as if after 40+ years the world has caught up with Monks and is ready to accept them. Not only do we have ‘Black Monk Time’ but we can now listen to the demos that lead up to it and, of course, this DVD that captures the full flavour of Monks and the times (then and now). And they have their legion of followers – see the ‘Silver Monk Time’ album (also on PlayLoud!) of covers by bands such as The Fall, Faust, The Raincoats etc. And we also have our very own Nuns – an all girls group dedicated to Monks’ music. It seems unlikely that Monks and their music will ever be ignored again. The DVD is great, both informative and enjoyable. It is no wonder that the film earned an award. It is recommended viewing, and not just for Monks fans. Monks were visionary. Monks are a revelation. I’m converted. Extras The extras offer over 70 minutes of treats – the outtakes of biographies from each member of the band help fill out their backgrounds; a session with David Day at home talking about his contributions and the banjo is funny, self-deprecating, and so full of life (it is sad that he died in 2008); and the live clips of Monks performing on German TV are a real treat – a chance to see just how dynamic they were on stage, and how challenging they were to the mainstream. Links: Http://www.playloud.org |

Comments